Introduction

The Stages Framework has been first introduced in June 2023 to provide clear and simple indicators of the maturity of a rollup, measured through the level of decentralization and trust minimization achieved by the project. The idea was first proposed by Vitalik Buterin on Ethereum Magicians in Nov 2022 and later made consistent and precise by the L2BEAT team. The Framework has been updated a few times since its inception, and it is expected to continue evolving as the ecosystem matures and new requirements emerge.

The rough intuition is as follows: Stage 0 represents a project who is fully controlled by few entities, Stage 2 represents a project that is fully controlled by code, and Stage 1 as something in between. Defining exactly what it means to be “in between” Stage 0 and Stage 2 is the major challenge of the Stages Framework, but extensive effort has been made to provide a clear and objective set of requirements.

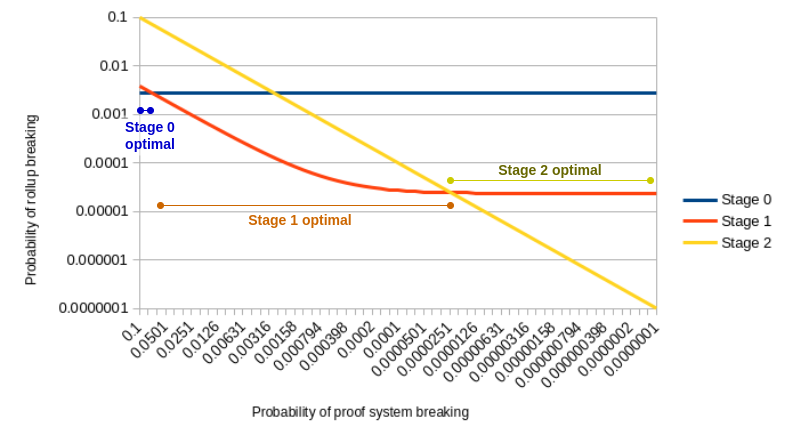

It’s important to note that the Stages Framework only discusses the maturity of a rollup in terms of decentralization, and not in terms of security. If a project is assumed to be bug-free, then the Framework can be seen as a measure of security against permissioned actors. In practice, it is very easy for a team to deploy a very unsafe but Stage 2 project, maybe because the proof system is very experimental or because contracts have not been properly audited. Decentralization is a proxy for security, including bug risk, only if the team decides to decentralize when the risk coming from permissioned operators becomes greater than the risk coming from bugs. Given some perceived probabilities of bugs and of actors being compromised, it is possible to compute what Stage guarantees the best security.

Taken from "The math of when stage 1 and stage 2 make sense" (2025) by Vitalik Buterin

Taken from "The math of when stage 1 and stage 2 make sense" (2025) by Vitalik Buterin

Perceived probabilities are subjective, and therefore users should always do their own research and decide whether the project is “mature” enough for its Stage designation. An orthogonal framework that better captures the notion of security from bugs is being researched, with the main challenge being how to scale reviewing audits (meta-auditing) for a large number of projects.

The requirements

🟥 Stage 0

Does the project call itself a rollup? To be considered a rollup, the project must self-identify as such. This requirement is straightforward and helps distinguish rollups from other type of projects that socially signal that they do not necessarily follow Ethereum consensus and might eventually deviate from it.

Are L2 state roots posted on L1? Posting state roots on L1 is a key characteristic of rollups that allows for withdrawals. If a rollup does not post state roots on L1, it falls short of a fundamental component of a bridged rollup.

Does the project provide Data Availability (DA) on L1? Ensuring data availability on L1 is essential for the security and reliability of a rollup. This means that all data necessary to reconstruct the L2 state must be available on L1, enhancing the system’s transparency and auditability.

Is software capable of reconstructing the rollup’s state source available? A rollup node software capable of reconstructing the L2 state from L1 data should be available, contributing significantly to transparency and trust. This allows anyone to review, audit, and run the software, enabling users and external observers to independently validate the proposed state roots against published data.

Does the project use a proper proof system? The proof system is used to adjudicate whether the proposed state root is correct or not. In the case of a fraud proof system, it allows invalid roots to be rejected. For zk rollups, the proof system is required to accept a proposed state root. If state diffs are used for data availability, the proof system must also ensure that all state changes are included in the diff.

Are there at least 5 external actors that can submit a fraud proof? A fraud proof system requires at least one honest actor to verify the correctness of proposed state roots and potentially dispute them. The fraud proof system must allow a minimum of 5 external actors to perform this task.

🟨 Stage 1

➡️ The only way (other than bugs) for a rollup to indefinitely block an L2→L1 message (e.g. a withdrawal) or push an invalid L2→L1 message (e.g. an invalid withdrawal) is by compromising ≥75% of the Security Council.

⚠️ Assumption: if the proposer set is open to anyone with enough resources, we assume at least one live proposer at any time (i.e. 1-of-N assumption with unbounded N). We don’t assume it to be non-censoring.

Upgrades initiated by entities outside of the Security Council are allowed if they provide at least a 7 days exit window.

Please refer to this forum post for a detailed explanation of the requirement and some examples.

🟩 Stage 2

Is the fraud proof system permissionless? In this stage, the fraud proof system should be fully decentralized and open to everyone. This means that anyone, not just a set of allowlisted actors, should be able to submit fraud proofs. This is a key requirement to ensure that the system is not controlled by a limited set of entities and instead is subject to the collective scrutiny of the entire community.

Do users have at least 30 days to exit in case of unwanted upgrades? Users should be provided with at least 30 days to exit the system in case of unwanted upgrades, including upgrades initiated by a DAO. This ample time frame allows users to react to significant changes in the system that they may not agree with and withdraw their assets if needed. One exception that we make is given the existence of a onchain bug detection system (e.g. two valid contradicting zk proofs), instant upgrades are allowed for detected bugs.

Is the Security Council restricted to act only due to errors detected on chain? In the final stage of rollup development, the power of the Security Council, if present, should be highly limited. It should only be able to promptly intervene in the case of adjudicable onchain bugs, which are serious flaws in the system that could cause significant harm if not addressed. By restricting the council’s emergency actions to these types of errors, the system becomes more decentralized and the trust placed in the Security Council is reduced. This moves the rollup further towards the ideal of trust minimization, where the code itself is the ultimate authority. An example of this feature is present in the Polygon zkEVM contracts, where the rollup goes in “Emergency Mode” if two different valid proofs can be submitted using the same batches.

Open questions

A number of edge cases have been identified for the Stages Framework, and we are actively working on clarifying them. Requirements for certain edge cases will be added as soon as some projects are discovered that fit them. The list of open questions can be found here.